I returned to the fire damaged house to

retrieve a set of books for this essay. The ones I have taken have brittle,

dark chocolate edges, and smell like the death of our cats. It was not an easy

task. There were two feline bodies outlined in soot upon the carpet and even

the blackened walls looked like they’d been crying. With a balled fist between

my teeth I willed the strength to fill up my car with the needed sorry remnants.

The Homeopathic Revolution by Dana

Ullman, was among them; a catalogue of 350 pages of famous people that have

turned to homeopathy to heal them since its discovery in the 18th

Century. Literary greats such as, Thoreau, Emerson, Longfellow, Stowe, James,

Alcott, Hawthorne, Irving, Twain, Goethe, Dosteovsky, Doyle, Shaw, Dickens,

Tennyson, JD Salinger and my personal favourite Gabriela García Márquez[1].

But it wasn’t any of these that filled my head with fantasies of writing a

novel about homeopathy. Instead the motivation was sparked on reading the

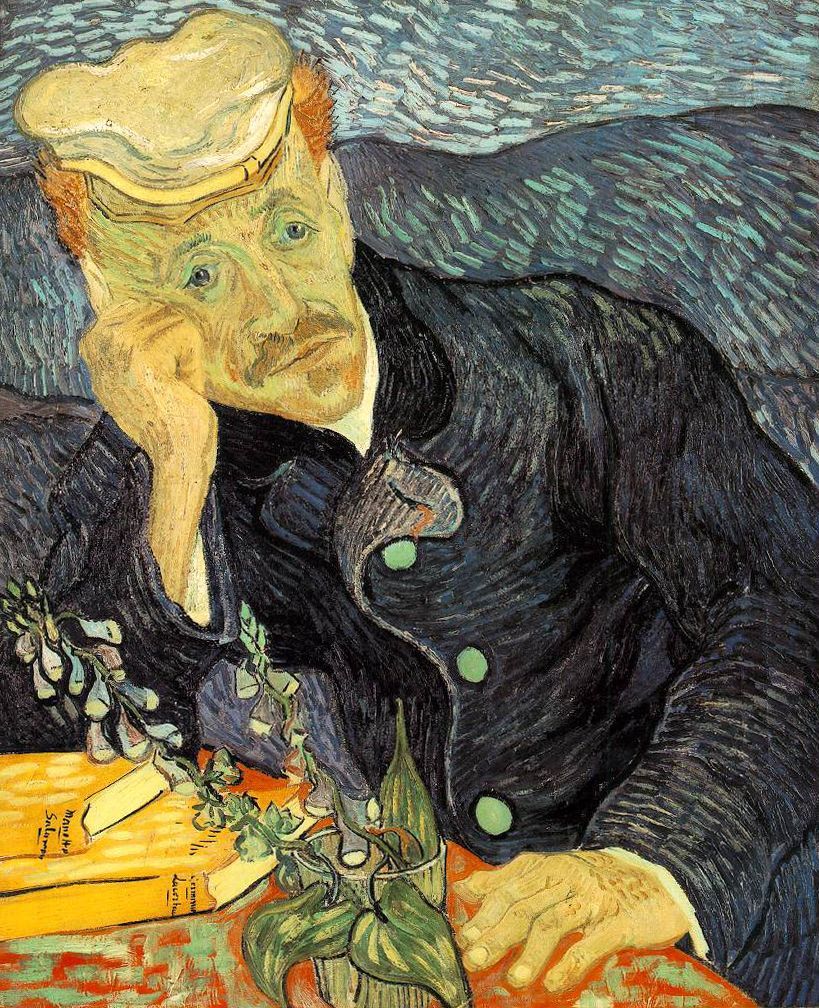

chapter Artists and Fashionistas where amongst the pages of the Impressionist

painters, Dr Paul Ferdinand Gachet struck my eye as a possible protagonist.

He was a

homeopathic practitioner and an amateur artist. His clientele was peppered with

a group of painters who conjugated in Paris in the latter part of the 19th

and the beginning of the 20th centuries. His patient list included

Edouard Manet, Claude Monet and most famously Vincent Van Gogh.[2]

Gachet is reported to have saved Camille Pissaro’s brother’s life, with

homeopathy, when allopathy failed to help.[3]

Being a

homeopath myself and having a personal interest in Ullman’s research and

reportage, I read The Homeopathic

Revolution in 2007 when it first came out. It was to be another two years

before my desire to write about Gachet finally materialised.

When my husband

died suddenly in July 2009, grief forced me into early retirement or an

extended sabbatical (life being what it is you can never really tell). I needed

to get through my days and I desperately craved to escape from reality. I began

to think seriously about beginning my first full-length novel.

I didn’t realise

it at the time but I had already collected quite a lot of research. Some of it stumbled

upon quite randomly, when, for example, one evening I tuned into Sky Arts to

discover a documentary about Edouard Manet’s masterpiece, Dejeuner sur l’Herbe. Manna

from heaven. My interest in this charismatic man was ignited through the

intriguing image of a naked Victorine Meurent, sitting on the grass, staring

out of the canvas, whilst surrounded by trees, water and strangely, two clothed

men who happened to be Manet’s brothers.

Even more

captivating is the story behind the work. Dejeuner

sur l’Herbe (pictured above) was ridiculed during its exhibition at the

Salon des Refusé in 1863[4].

This event alone was responsible for propelling the artist to fame. I already knew

that Manet was an acquaintance of Gachet and that they both took part in Parisian

café society.

Rebel in

a Frock Coat by Beth Archer Brombert, a biography on Manet, informed me that

he was not just controversial and mysterious in his artistry, but he was also

enigmatic in his private life too. He lived half the week with his mother in

their family apartment in one of the most prestigious roads in Paris, and for

the other half he lived with Suzanne Leenhoff in a bourgeois home on the other

side of the Seine. When he stayed with his mother he attended soirées, was

charming and witty and definitely a ladies man. Suzanne was unfashionable and

considerably older than Manet. She had been his piano teacher when he was a

child. There was a boy called Leon who also stayed in the apartment. Brombert believed

that Leon was Suzanne and Manet’s son, mainly because at the end of Manet’s

life he included the boy in his will. In the writing of Mesmerised,

I explored a more shocking possibility for Leon’s ancestry, based on a rumour

that Brombert also refers to in her book.[5]

My fascination

for the era and Gachet’s world had taken its hold upon my imagination. I went

to Paris many times, traced the route from Gachet’s apartment in rue Faubourg

Saint Denis to the Boulevard des Italiens where many of the cafés were

situated. I stood outside his apartment and

imagined overhearing the residents in the courtyard behind the large, royal

blue door. I explored the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay, and hunted for Blanche’s

house (Gachet’s sweetheart), which I eventually found close by the Quai d’Orsay.

I ambled along the embankment to Victorine Meurent’s studio in the narrow

cobbled lane of rue Mâitre Albert.

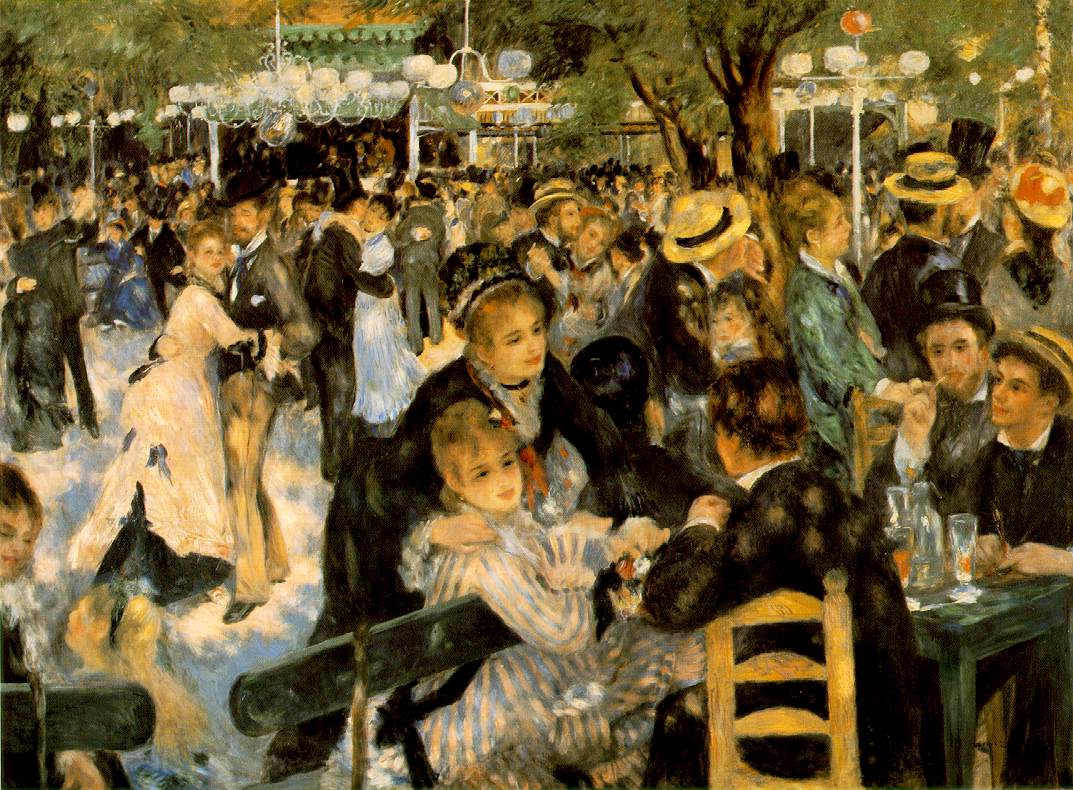

My hotel was near

Pigalle, almost opposite Le Moulin Rouge which was built after the time I write

about in my book, but nevertheless infuses me with a certain mood, one that

carries the scent of tart au citron, Arabian coffee and patchouli. I climbed

the steep steps up to Montmartre and drank wine overlooking the square. I

watched street artists set up their easels and draw caricatures of tourists.

There is a restaurant that sells beer, moules frites and onion soup from the

plâts du jour on the very site, I imagine, of Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette (below).

When I

discovered that there was to be a festival in Auvers sur Oise to celebrate one

hundred years since the death of Dr Gachet, it appeared to me like another gift

from the gods. A wonderful opportunity

to soak in the atmosphere of the village where Gachet lived as a family man and

where his friend and patient Vincent van Gogh came to stay and died. So, I went

back to Paris and took the train.

How wonderful to have seen the garden famously

painted by Cezannes - Gachet’s neighbour - with the section where Gachet grew his own

medicines. I was enchanted too, by the restaurant where visiting artists came

together to drink and dine, a place that’s been preserved museum-like. And chilled

by the spot outside the church up in the hills where van Gogh shot himself and

the spartan room where he later died.

On reading around my subject I found:

Portrait

of Dr Gachet (picture at the start of this essay) by

Cynthia Saltzman, which told the story of the van Gogh masterpiece, at one time

the most expensive painting in the world[6].

Alias Olympia by Eunice Lipton, a quirky

biography of Manet’s model Victorine Meurent[7].

Zola’s The Masterpiece[8]

and L’Assomoir[9],

both of which allowed me to immerse myself in the eloquence of one who had

lived the time and place.

A book lent to

me by a very cool, very young, artist friend of mine called The Private Lives of the Impressionists by

Sue Roe which collated many anecdotes and brought characters to life.

So that when my friends

in the Nomads writer’s group started presenting the beginnings of their novels

and encouraged me to do the same, I was ready, but nevertheless felt weighted

down my own high expectation for the text.

Nevertheless, on

a cold and miserable October day, I began the novel, and each subsequent day I

was lured to the keyboard by a world that I found delicious. I was overwhelmed

by the drama that was playing within my mind. It was the perfect antidote to my

sadness. My therapy.

Post-it notes

soon mushroomed all over my desk with ideas for scenes, subplots, conversations

and sometimes, just sentences or isolated words. Behind my desk I created a collage

that included portraits of the characters, images of Manet’s paintings Dejeuner sur l’Herbe and Olympia (below), a map of Paris that I referred to many, many times, plus

photographs of places that appear in the book.

The hospital, La Salpêtrière, for example, which

amazingly, is exactly how I envisioned it, down to what I had come to think of

as ‘Gachet’s tree’, right there in the middle of the grounds. The hospital

today is on an avenue just outside the main environs of Paris. In the mid

nineteenth century it would have stood in a more rural setting.

Then there are Michelangelo’s

marble sculptures, Slaves (below), in

the Louvre.

I sat before

them for hours on a bum-numbing wooden bench and observed how the light played

on the statues and on the floor at various times of day. I listened to the

sounds of visitor’s footsteps and whisperings and tried to discern the hall’s

unique smell. When I took the photograph I knew that there would come a time

when my elite group of artists, or some of them anyway, would go there to

sketch.

Blanche’s house

behind the Assemblée Nationale was a lucky find. I had already started to write

scenes and imagined the whitewashed terraced house with a bench outside and

tubs of flowers to either side of the front door. A friend of mine who lived in

Paris for many years and one of my early readers had told me that no such house

exists in France’s capital city. If I hadn’t discovered it for myself I would

have felt compelled to change its appearance in the story. I had such a clear

image of it in my mind that to do so would have been to go against my finer

instinct. But as Gachet says at the beginning of chapter five, ‘I don’t believe

in coincidence. I believe forces of the universe dictate when certain fates

collide.’

There was a time

when I wanted to write a contemporary, political thriller that challenges the

myth that homeopathy cannot possibly work. This is a belief perpetuated by a

group of eminent medics who rally on the side of the pharmaceutical industry

and a current situation that led me to mastermind the original Homeopathy Worked for Me campaign in 2006[10].

The main premise

of my story was to be a healing process, one that is refuted by science, but

nevertheless confirmed through the eyes of a homeopath; a child’s autism

reversed by homeopathic medicine as written about by Amy Lansky in her biography

The Impossible Cure[11].

I began the

narrative several times in different ways but found my own prejudices creeping

overtly into the text, and because of this, each attempt was subsequently thwarted.

On reading

Clemens van Boenninghausen’s writings (Gachet’s mentor in Mesmerised) I began to understand that the

political situation concerning homeopathy then, was not dissimilar to how it is

today. Knowing that Gachet had written about nervous disorders and that he worked

at La Salpêtrière helped me to transport my original idea into the past. But instead

of autism the patient’s diagnosis in Mesmerised is mania and madness - what now would be termed schizophrenia and acute

psychosis - two pathologies that I have worked with extensively in my own

homeopathic practice.

I was also able

to draw a parallel between homeopathy and Impressionism, both similarly frowned

upon by their respective governing bodies in mid-nineteenth century Paris. A

circumstance that forced practitioners of these two pursuits to live outside

the accepted boundaries of society, determined to continue doing what they

believed in and what they thought was right.

Both homeopathy and Impressionism are concerned with making manifest

what lies hidden beneath the surface. They explore depths, seek out essences,

and hold a mirror up to the world in a quest to find harmony. The two practices

make perfect bedfellows, especially at that time in history, for these days, although

homeopathy is still derided, Impressionist art is now lauded for having been avant-garde.

Before I began Mesmerised, I had a vision of how

I wanted the final book to be; the type of writing, the language, and the world

both real and imagined. On reflection I can see some of the influences that

have paved the way for me: D. H.

Lawrence who was unashamedly uninhibited and controversial in his writing[12].

Philippa Gregory who did not censor her imagination when it came to depicting

Anne Boleyn in Tbe Other Boleyn Girl[13].

Ian Mc Ewan, whose characters in Atonement

are believably historic but also, somehow, modern [14].

Rose Tremain who in Restoration, found

a political parallel in former times; ‘Restoration

was built on high Thatcherism…’, she is reported to have said.[15]

The structure of Mesmerised is a simple one, as

I was writing, the main plot seemed to weave naturally around true events that happened,

predominantly, in 1863. But the biggest challenge was making sure the

homeopathy was right, not too complicated but also not banal. It helped having

studied the work of Rajan Sankaran[16],

a man who is on a lifelong quest to grasp the full extent of homeopathy.

Involving his knowledge of nature in his observations makes his books so much

more than just a lesson in homeopathy. His effect on my clinical understanding

is indelibly sewn into the writing of Mesmerised. I am most conscious of using

An Insight into Plants[17],

The Soul of Remedies[18]

and Structure[19]

for greater understanding of remedies, Phosphorous,

Ignatia, Belladonna, Platina and

Veratrum Album, all of which were prescribed by Gachet in my book.

During my visit

to Gachet's house, I was informed by a steward, that most evenings Gachet sat in an

arm chair reading Samuel Hahnemann’s Organon[20]

and The Chronic Diseases[21].

The thought of this made me smile; like myself, he was an earnest practitioner.

It was quite

early on in the novel’s conception that I decided to use aphorisms from the

above works to head and be pertinent to some of the diary entries . April 17th, for example, whilst Dr Jean-Martin Charcot intoxicates students with his demonstrations of hypnotherapy, I chose aphorism 1 from the Organon of Medicine as an introduction:

The Physician's high and only mission is to restore the sick to health, to cure, as it is termed.

When I wrote the

homeopathic textbook What About the

Potency?[22]

I took time away from a busy practice to do it. I had a few scribbled notes and

a huge amount of concern about my ability to articulate what I had learned

through experience. A nagging feeling in my solar plexus kept urging me to try.

So I ran with it. Today, What About the

Potency? is on the required reading

list at the Centre for Homeopathic Education in London, has sold all over the

world and is now into its 3rd edition.

That feeling in

my solar plexus was also there during the writing of Mesmerised. The creation of Mesmerised was a much needed

joyful experience, in an otherwise cruel, and difficult time in my life.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beth Archer Brombert, Rebel in a Frock Coat, 1997

Philippa Gregory, The Other Boleyn Girl, 2002

Samuel Hahnemann, Organon of Medicine, 1810

Samuel Hehnemann, The Chronic Diseases, 1835

D. H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Love, 1928

Eunice Lipton, Alias Olympia, 1992

Ian McEwan, Atonement, 2001

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, 2006

Cynthia Saltzman, Portrait of Dr Gachet, 1999

Rajan Sankaran, The Soul of Remedies, 1997

Rajan Sankaran, An Insight into Plants, 2007

Rajan Sankaran, Structure, 2008

Michelle Shine, What About the Potency, 2004

Irving Stone, Depths of Glory, 1983

Dana Ullman, The Homeopathic Revolution, 2007

Émile Zola, L’Asshommoir, 1876

Émile Zola, The Masterpiece, 1886

[1]

Ullman, Dana, MPH (North Atlantic Books, 2007) The Homeopathic Revolution, p63

[2] The Homeopathic Revolution, p 173

[3]

Stone, Irving (Mandarin Paperbacks, 1990) Depths

of Glory, p203

[4] Roe, Sue (Vintage, 2007) The Private Lives of the Impressionists,

p27-29

[5]

Brombert, Beth Archer (The University of Chicago Press, 1997) Rebel in a Frock Coat.

[6] Saltzman, Cynthia (Penguin Books

Ltd, 1999) Portrait of Dr Gachet

[7] Lipton, Eunice (Cornell University

Press, 1999) Alias Olympia

[8] Zola, Émile (Oxford University

Press, 2008) The Masterpiece

[9] Zola, Émile (Penguin Books Ltd,

1970) L’Assommoir

[10] http://www.homeopathyworkedforme.org/#/impurities/4531876745.

[12] Lawrence, D. H. (Wordsworth

Editions, 2007) Lady Chatterley’s Lover

[13]

Gregory, Philippa (Harper 2007) The Other

Boleyn Girl

[14]

McEwan, Ian. (First Anchor Books Edition, 2003) Atonement

[15] http://jasonbye.com/the-times-interview-with-author-rose-tremain/

[16] http://www.rajansankaran.com/

[17]

Dr Sankaran, Rajan

(Homeopathic Medical Publishers, 2007) An

Insight into Plants

[18]

Dr Sankaran, Rajan (Homeopathic Medical Publishers, 1997) The Soul of Remedies

[19] Dr Sankaran, Rajan (Homeopathic

Medical Publishers, 2008) Structure

[20] Hahnemann, Samuel (B. Jain

Publishers Limited, 1988) Organon of

Medicine

[21] Hahnemann, Samuel (B. Jain

Publishers Limited, 1835) The Chronic

Diseases

[22] Shine, Michelle (Food for Thought

Publications, 2011) What About the

Potency?